Co-Creating the Classroom: Collaborative Ground Rules for Engaged Learning

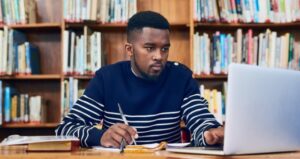

Teaching in higher education involves far more than delivering content. It means cultivating an inclusive and participatory environment where students feel seen, valued, and empowered